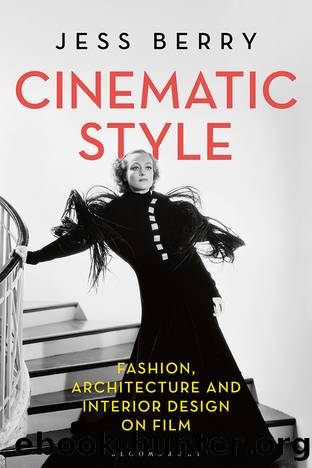

Cinematic Style by Jess Berry

Author:Jess Berry

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Figure 5.1 Selfridges windows lit up at night (1935). Photo Credit: David Savill/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images.

Selfridgesâ windows â much like other department stores of the era â offered women a form of self-fulfilment, by providing a legitimate mode of independent access to the public spaces of metropolitan culture. They also played an important role in the suffrage movement in England, providing a space for political engagement on the streets. Selfridge was a supporter of womenâs rights, underwriting feminist publications, encouraging protest organizers to meet in the store and displaying suffragette colours in the storeâs windows. Perhaps recognizing that support of the movement could also make him money, Selfridge stocked the white dresses that suffragettes adopted as their uniform. When in March 1912 women protesters broke the windows of almost 400 shops, including said department store, Selfridges did not press charges.11

As the case of Selfridges demonstrates, the shop window, like cinema, complicates understandings of the relationship between women and consumer culture. As outlined in Chapter 1, according to much feminist film analysis, cinema contributes to the condition where the female spectator is encouraged to participate in her own objectification and commodification while aligning herself to cultures of consumption.12 Just as cinema offered women opportunities to consider modern identities that enacted forms of liberation and agency through mobility and self-determination, shop windows both enticed women to engage in consumption and offered opportunities for new forms of social engagement in urban life. Film historian Lauren Rabinovitz provocatively suggests that reflections in shop windows allowed for a female spectatorship â where women could participate in acts of looking not only at commodities on display, but also at herself in relation to other people participating in the urban environment. Cinema, as a development of the shop-window gaze,

extended the legitimate public space for women to look, and it expanded their possibilities of a mobilized wandering gaze from the restrictive zone of the street window and department store to new virtual territories.13

The cinematic effect of shop windows can also be uncovered in Walter Benjaminâs writings in the allusive montage of thoughts that is the Arcades Project.14 The covered shopping passages of nineteenth-century Paris provided Benjamin with an allegory for his investigation into the spectres of modernity. Drawing on Marxist theories of commodity fetishism, Benjamin proposes the commodity on display as a phantasmagoria â a spectacle of illusion that enthrals the bourgeois class through unobtainable dream-like images and experiences that mask the ârealityâ of everyday life. Identifying window shopping as the act of the male flâneur in search of sensation, the phantasmagoric effects of the arcade provided pleasure in looking, through a constellation of temporal associations.15 Obliquely drawing connections between the arcade as the precursor to department stores, fashion as a structure that presides over commodity fetishism and interior spaces as phantasmagorical experiences, Benjamin brings together these âresidues of a dream worldâ, as the constituents of a mobilized gaze of urban spectatorship.16

Film studies scholar, Anne Friedberg draws parallels between Benjaminâs experience of the arcade as a temporal movement

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Designers | Fashion Photography |

| History | Models |

Tokyo Geek's Guide: Manga, Anime, Gaming, Cosplay, Toys, Idols & More - The Ultimate Guide to Japan's Otaku Culture by Simone Gianni(2352)

Batik by Rudolf Smend(2163)

Life of Elizabeth I by Alison Weir(2066)

Vogue on: Dolce & Gabbana by Luke Leitch(1652)

The Little Book of Bettie by Tori Rodriguez & Dita von Teese(1649)

Vogue on: Manolo Blahnik by Chloe Fox(1570)

Paris Undressed by Kathryn Kemp-Griffin(1467)

How to Dress by Alexandra Fullerton(1393)

A Victorian Lady's Guide to Fashion and Beauty by Mimi Matthews(1389)

Pretty Iconic by Sali Hughes(1338)

Indigo by Catherine E. McKinley(1274)

The Light of the World by Elizabeth Alexander(1251)

101 Things I Learned in Law School by Matthew Frederick(1207)

The Language of Fashion by Barthes Roland(1180)

Lazy Perfection by Jenny Patinkin(1173)

Fashion Victims by Alison Matthews David(1158)

Architecture by Davis Amy(1151)

Fashion Illustration 1920-1950 by Walter T. Foster(1148)

House of Versace: The Untold Story of Genius, Murder, and Survival by Ball Deborah(1139)